There's a story you can tell about European soccer where defensive midfielders explain the world.

Per ESPN BET's odds, three teams have at least a 10% chance of winning the Champions League this season: Manchester City, Real Madrid, and Arsenal. Those three teams employ, arguably, the three best defensive midfielders in the world: Rodri, Aurélien Tchouaméni, and Declan Rice. Quibble with the specifics if you want, but the crowd-sourced valuations from Transfermarkt have those three as the only players at their position with nine-figure transfer values.

Fourth in the Champions League odds: Liverpool, who have tried and failed in three successive summers to sign big-money holding midfielders. Fifth favorites: Barcelona, who have been swaying in the wind since Sergio Busquets left the club last summer. Tied with Barca are Bayern Munich, who spent two straight summer transfer windows trying to acquire Fulham's late-20's defensive midfielder.

Seventh: Paris Saint-Germain, who still haven't found a holding midfielder they trust for the long haul. And the only other team with title odds of at least 5%: Inter Milan, who dominated Serie A last season by playing without a true holding midfielder, but went out early in the Champions League because they couldn't control a two-goal lead against Atletico Madrid.

At the highest level of the sport, you have three teams anchored by without-a-doubt world-class defensive midfielders -- and then five others whose recent existence seems to be defined by the fact they do not have a world-class defensive midfielder on their roster.

So, what do these players do that's so important to winning soccer games? Why are they becoming more expensive to sign? And are they really as important as they seem based on all the facts just laid out?

What does a defensive midfielder actually do?

The simplest way to sum up why these players are so rare is that they're expected to win the ball frequently and pass the ball frequently. In other words, they're tasked with two responsibilities that almost have no connection with each other.

Outside of some kind of anticipatory vision that helps you see where to pass to and when to attempt a tackle, there's really no crossover between the skills that make you a good defender and the skills that make you a good passer.

You could even make the argument that the skills actually go against each other. To win tackles, you need a certain amount of strength and athleticism and size. And across pretty much every sport, there seems to be something of an inverse relationship between those things and creative skill with the ball itself.

To put some numbers on this, let's look at what defensive midfielders do for the best teams in the world. Opta ranks every professional soccer team in the world, with the best team getting a power-rating of 100 and the worst landing at zero. For teams with a rating of 90 or above last season across the Big Five European leagues, their defensive midfielders:

• Made 5.45 tackles and interceptions per every 1,000 opponent touches

• Recovered 5.9 loose balls per 90 minutes

• Played 70.4 passes per 90 minutes

• Completed 90.3% of those passes

Among all the positions classified by Stats Perform, those numbers ranked first, first, second, and second. No one else won or recovered the ball more often among these teams, and only center-backs played and completed more passes than the defensive midfielders did. Those are also basically the season-long stats for Inter Milan's Hakan Çalhanoglu -- a converted attacking midfielder.

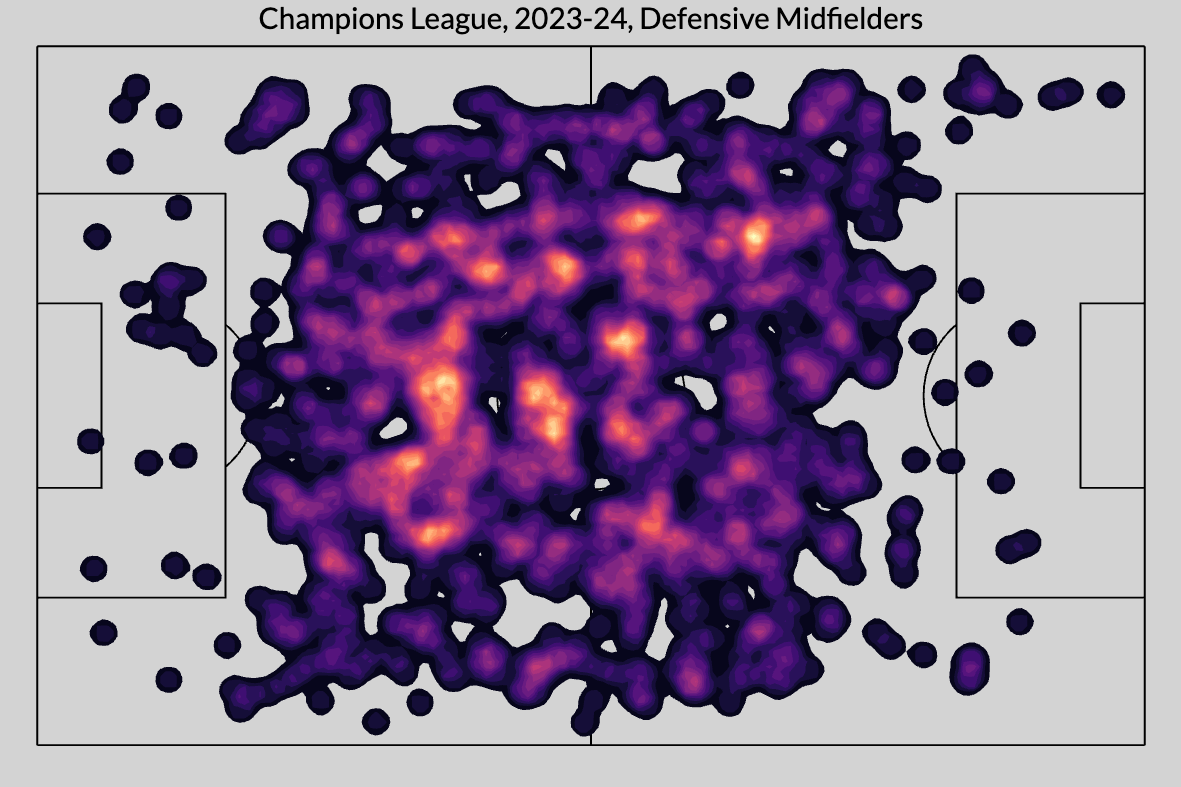

Here's a heatmap of where all the defensive midfielders played their passes from in the Champions League last season:

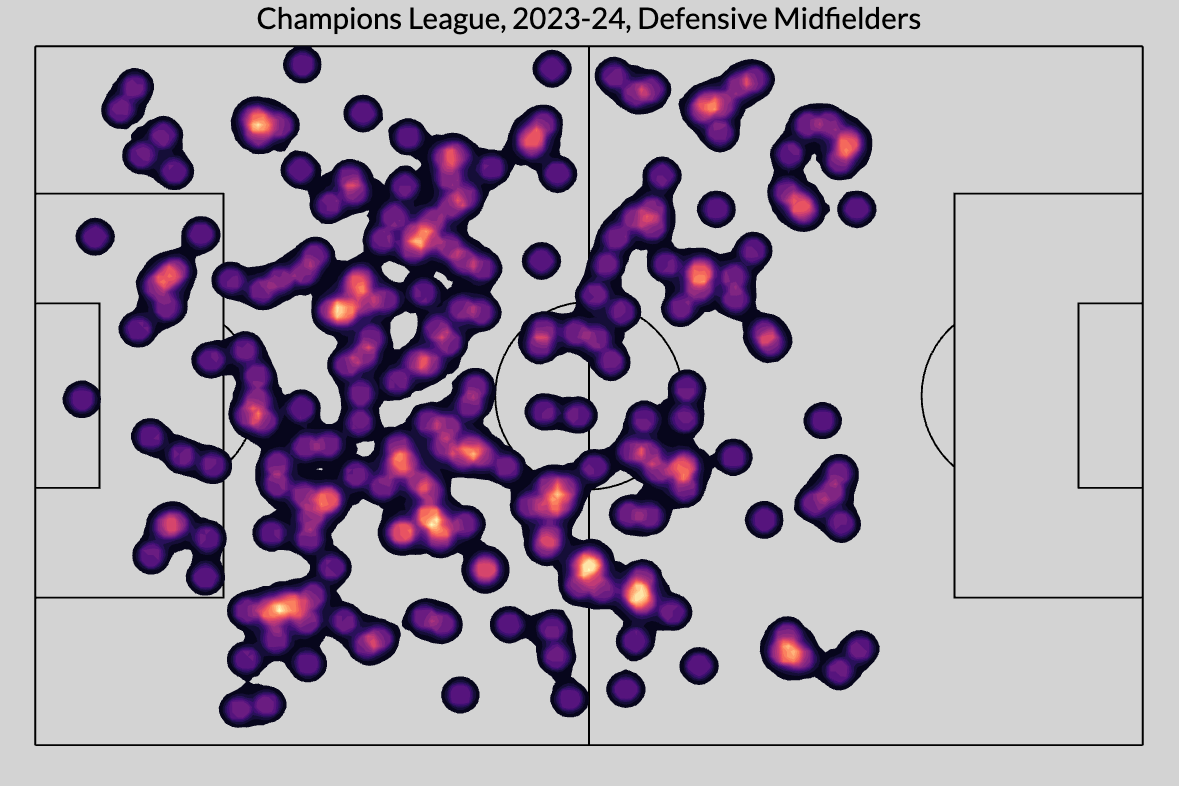

And here's where they made tackles, intercepted passes, and recovered loose balls:

Almost everything they're doing, then, occurs in the least valuable area of the field.

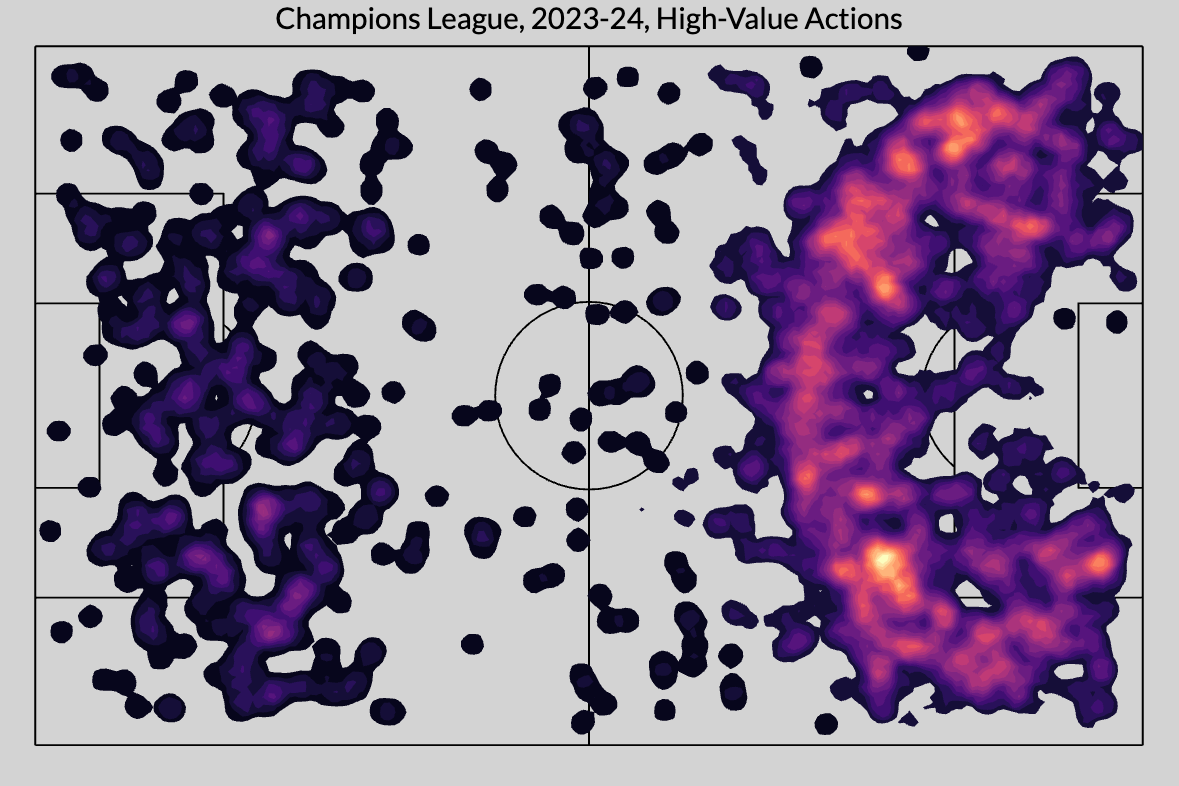

Opta's possession-value model determines how much every on-ball action increases or decreases a team's chances of scoring a goal within the next 10 seconds. Here's a heatmap of everything from the Champions League last year that increased a team's chances of scoring by at least 1%:

You see a ton of stuff around the attacking penalty area then another load of actions around and inside the defensive penalty area. Take a step back, and it makes sense: Penalties are converted at least 75% of the time, so whenever a ball moves into the box, it's not only moving closer to the goal but it's also enabling the possibility of a penalty, which is way more valuable than any other chance you're likely to see over the course of a given match.

Anything that shifts the ball into the penalty area will greatly increase goal probability. And the inverse is true on the other end: When the other team is near your goal, they're likely to score, so if you dispossess them of the ball, you're deflating their goal-scoring probability and increasing yours.

To sum it all up, the job of a defensive midfielder on a top team is to (1) prevent the opposition from getting into dangerous areas in the first place, and (2) get the ball into positions from where their teammates can then move it into dangerous areas.

Declan Rice, Chelsea, and the rise of the $100-million defensive midfielder

Something seemed to shift after the 2021-22 season, perhaps the first "normal" campaign after the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic.

That summer, Real Madrid paid €80 million in transfer fees to Monaco to acquire 22-year-old defensive midfielder Aurélien Tchouaméni. Later that summer, they allowed the player he was replacing, 30-year-old Casemiro, to depart to Manchester United, who paid €71 million to get him out of his contract. The previous record fee paid for a player at this position was Manchester City's €70-million-move for Atletico Madrid's Rodi in the summer of 2019.

Then, the following winter, both of those moves were left in the dust. After Enzo Fernández's World Cup-winning performance as the deepest midfielder for Argentina, Chelsea paid €121 million to acquire the 22-year-old from Benfica, who themselves had paid €45 million to acquire him from River Plate just six months earlier.

Not happy with only one expensive defensive midfielder, Chelsea then went out and acquired two more the next summer, paying €116 million for 21-year-old Moisés Caicedo from Brighton and €62.1 million for 19-year-old Romeo Lavia from Southampton. Arsenal brought in Declan Rice for €116.6 million that same summer, and 22-year-old Manuel Ugarte moved to PSG for €60 million.

The consultancy Twenty First Group uses a number of historical factors to predict a player's transfer value, and over this stretch they've found that clubs have paid 21% more than you'd expect for defensive midfielders. Based on the estimates from Transfermarkt at the time, these seven players had a combined market value of €392 million. Their new teams paid €626.7-- a 62.5% markup from the crowd-sourced valuations.

The spending trend has continued this summer. PSG probably will be sending Ugarte to Manchester United for around €60 million after replacing him with Benfica's 19-year-old João Neves for about the same fee. Aston Villa acquired Amadou Onana from Everton for €59.4 million. And Bayern Munich brought in the afore-alluded-to João Palhinha for €51 million.

While these don't match the same high-end fees of previous seasons, they all seem high once put into context: Neves is quite young, Ugarte never became a reliable starter at PSG, Onana has never played at a Champions League level, and Palhinha might already be past his prime.

Remember, all of these fees are being devoted to players who don't really do all that much in either of the most valuable areas on the field.

So, are defensive midfielders actually overrated?

It's quite easy to come to a conclusion that defensive midfielders are overvalued -- but it's just as easy to conclude that they are undervalued.

There are six players at this position who commanded fees of at least €70 million. Three of them were massive successes: Rodri might win the Ballon d'Or soon, Rice is arguably Arsenal's most important player, and Tchouaméni is going to anchor the midfield for Real Madrid for a decade.

The other three? Not so much. Although Enzo looked fantastic in his first half-season with Chelsea, it didn't translate to winning on the field, and he hasn't hit the same individual levels since. Caicedo has been inconsistent, and his impact on Chelsea's performance, too, is quite hard to pinpoint. Casemiro, meanwhile, had one good season and one awful season for Man United -- he's presumably about to be replaced by Ugarte.

Drop below the €70 million tier, and the results are similarly mixed: some successes, some flops, some mixed bags, and some too early to tell. The truth is that it's really hard to reliably and accurately quantify midfield performance. So hard, in fact, that there's an entire chapter in my book, "Net Gains," about it.

Let's go back to that possession-value stat from earlier. Let's say you're a lesser-known member of a royal family in control of a valuable natural resource and you've been allowed to purchase a Premier League team with some of your family's sovereign wealth. Let's say, you've, I don't know, read "Net Gains." And let's say you want to run your team using only analytics so you don't get swayed by all the cognitive biases that come with scouting players. So, you decide to hoard all of the players who are best at increasing their team's chances of scoring a goal.

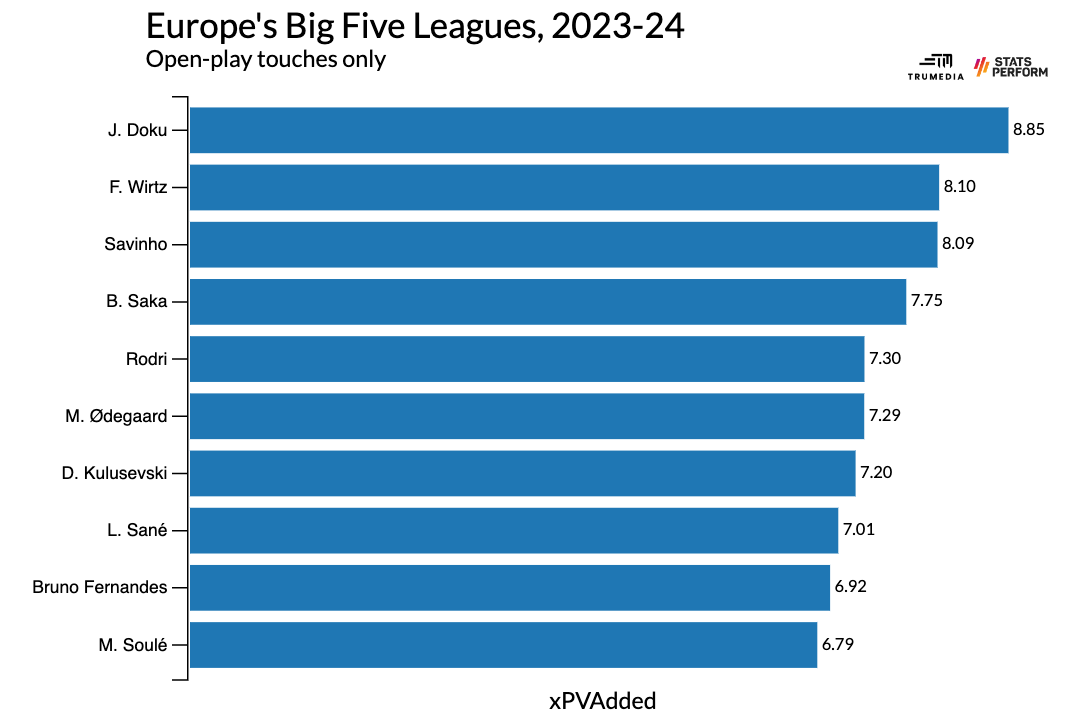

If you did that, your team would stink. Here are the top 10 players in possession value added across Europe's "Big Five" top leagues from last season:

You'd have Rodri, and then nine attacking midfielders and wingers. Would it be fun to watch? Absolutely. Would it work? Absolutely not.

There's clearly some kind of offense-to-defense spectrum here, and if you look at everything in terms of goal probability, you'd be missing a vital piece of information about how soccer works. This is why Rodri deserves to be rated so highly. Despite playing in a position almost designed to not create analytical value, he still creates a ton of value while also doing all of the hidden things defensive midfielders do that can't be picked up by a model looking only at what's happening with the ball.

At the same time, I can't help but think there might be some kind of lesson to be learned. And front-office sources in Europe have suggested as much to me. Of course you don't want Bruno Fernandes playing right back and Savinho at center-back, but maybe teams should be more aggressive in their player selection and team construction.

Gab Marcotti, Mark Ogden and Ryan O'Hanlon discuss Aston Villa's draw upon their return to elite European football.

Despite all of their continued efforts to acquire one -- first Tchouaméni, then Caiceo and Lavia, and then Real Sociedad's Martín Zubimendi this summer -- Liverpool didn't play a recognized defensive midfielder for much of last season ... and they were favorites to win the Premier League with fewer than 10 matches to go. Inter Milan did the same -- and won 94 points en route to another Serie A victory. For all the defensive trade-offs of not having one of these players, there's also an attacking benefit to dropping a more creative midfielder deeper on the field.

This is all within the environment where defensive-midfield costs are massively inflated. If you can avoid overpaying in that area, you'll have more resources to strengthen other parts of the field where the fees haven't risen so much. Per Twenty First Group's projections, regular central midfielders have been undervalued by about 5% in recent windows.

The tactical history of team sports is a history of decision-makers being way too conservative and only slowly realizing that and then adjusting. But I think the current tactical environment at the top of European soccer has become more conservative recently.

Teams are no longer having both of their fullbacks push high -- instead at least one will pinch next to the center-backs to form a lopsided back three in possession. To me, this would seem to lessen the need for a do-everything defensive midfielder.

When Fernandinho played this role at Man City, he typically had only two center backs behind him for cover. With Rodri in the same spot, he frequently has three defenders behind him, and City's fourth fullback, too, is usually a converted center back -- much more of a defensive contributor than an attacking piece. One of the unquantifiable parts of defensive-midfield play in the past was that a great one, with his ability to cover so much ground off the ball, allowed you to jam more attackers onto the field. The modern possession structure negates that benefit.

Given the tactical and economic contexts, there are two possibilities here. The first: this new, more conservative positioning on the ball and these defensive-midfielder fees are both optimal. The former is the best way to play soccer and the latter is the best way to build a team. Or, there's the second and much more likely possibility: There are different ways to play and players to value that would produce equivalent, if not better, results.

Soccer has never been solved -- it never will be in the way that baseball was -- and there are always disruptions to the tactical era of the day that exploit its weaknesses and make it untenable. There's a financial and a tactical opportunity here for anyone who's willing to be different and perhaps find a way to fit more players onto the field who contribute around the penalty areas.

It's not as if the successes of Rodri, Rice, or Tchouaméni negate this idea, either. The first two combined for 15 goals and 17 assists in the league last season, while the latter spent much of the season playing as a makeshift center back. Even for the three best defensive midfielders in the world, they still help their teams win by scoring, creating, and preventing goals.